Fading Landmark Seeks Future in Harlem

With the real-estate market in Harlem on the rebound, the city is hoping a long-abandoned sore spot in the area will become a hot spot for potential developers.

The Corn Exchange Building—or what’s left of the historic structure at East 125th Street and Park Avenue—is up for grabs. Potential buyers have until April 22 to come up with proposals for the prime, but beleaguered, site.

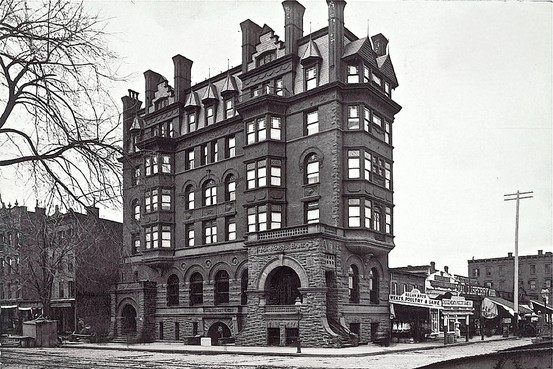

Built in 1883 as the Mount Morris Bank, the building was the pride of Harlem with its gables and rich terra-cotta ornament. The Romanesque Revival-style building included luxury apartments, and was an emblem of the neighborhood’s prosperity.

But today, after years of damage, much of what made the building special is gone. “You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who remembers it any other way than a monument to faded glory,” said Simeon Bankoff, executive director of Historic Districts Council, who has advocated preserving the building.

Despite its auspicious beginnings, the building has been long troubled. It became the Corn Exchange Bank in 1913, merged with Chemical Bank in 1954 and eventually ceased operations.

It was acquired by the city in 1972 and designated a city landmark in 1993, but the building has languished. A 1997 fire destroyed the top stories, including the mansard, of what was originally a six-story structure.

In 2009, the Department of Buildings removed two more floors of the building as an emergency measure after finding the structure was unstable. Matthew Washington, chairman of Community Board 11, which serves East Harlem, recalls that the demolition work was done without public debate and over preservationists’ objections.

Then in March, the city’s Economic Development Corp., which regained title of the building after selling it to a failed nonprofit, asked developers for expressions of interest about what to do with the once-grand building. Community leaders were again surprised by the move.

“When I found out [the request to developers] was going out, I said, ‘Wait a second, we didn’t hear anything about this,'” Mr. Washington said.

This time, he said, the community is determined to weigh in on proposals for the property.

Spokesman Kyle Sklerov of the Economic Development Corp. said the request is the first review “just to see what people come up with for ideas” and that “moving forward, we will be getting feedback from the community.” The selected plan is subject for review by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Advocates of the building see a variety of possibilities for the 4,500-square-foot property, including cultural, residential or retail uses. Mr. Washington said he’d like to see a youth-oriented facility there—such as a basketball court or an indoor pool.

Garry Anthony Johnson, who formerly served on the community board’s economic development committee, imagines a boutique hotel created inside the structure, in much the way the New York Palace Hotel was incorporated into the landmarked Villard Houses on Madison Avenue. The remains of the bank building are structurally sound, said Mr. Johnson.

Community leaders know what they don’t want: more glass towers or big box stores. Marina Ortiz, founder of East Harlem Preservation Inc., said she would like to see development that gives the community control.

“We don’t want to go through the motions and be told, ‘We know better than you,'” she said. “I’d like to see something that captures some of Ethel Bates’s vision—a locally owned and operated institution that supports the community and provides jobs at more than living wages.”

Ethel Bates is the community activist who acquired the Corn Exchange in 2003 with a plan for a nonprofit culinary school at the site. When Ms. Bates lost backing for the projected $9 million restoration, the building, quite literally, fell to pieces.

A series of lawsuits filed by the city and a bankruptcy filing by Ms. Bates halted her plans. She has filed an appeal to the state Supreme Court’s decision that returned the property to Economic Development Corp.

Ms. Bates said she was unable to comment while the appeal was under way.

Mr. Johnson is keeping a close watch on the site, literally: His architectural office sits directly across the street from the building. Mr. Johnson was a critic of the 2009 partial demolition and worries about the site’s future.

“I’m not antidevelopment,” he said. “I’m pro-development that’s controlled and respectful.”