In the Society of Dead Masons

WHEN late-winter temperatures break 32, the Park Avenue railroad viaduct calls to mind a weeping statue of a saint, teardrops of meltwater dripping from the battered stone along the massive walls, which extend from 98th to 111th Street. And the strange series of letters and symbols running all the way along the 1875 structure is just as otherworldly — as mysterious as messages from another planet.

The railroad along Park Avenue was chartered in 1831 by Harlem landowners and others who wanted better downtown connections. Below 96th Street the city grew up around the tracks, and pressure grew to sink and cover them. The railroad wanted to build a platform over the street from Grand Central to Harlem, but it finally agreed to the more expensive alternative, sinking the tracks for most of the length, beginning in 1872.

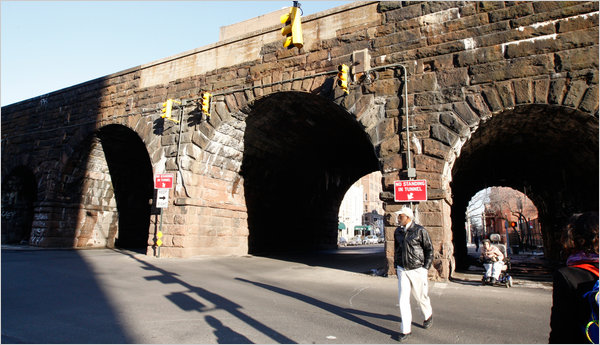

North of 98th Street, where the land was low and swampy, the tracks rode on a wooden trestle for almost a mile. Over this stretch, from 98th to 116th (but since reduced), the railroad built the massive stone viaduct, with 2,000 men at work, night and day, from 1872 to 1875.

The remains of a mezzanine-level local station are still visible at 110th Street, and arches over each cross street are formed from brownstone taken from Portland, Conn. The long walls in between were built in a puzzling mix of stones, as if they didn’t matter, including Westchester gneiss and granite from Stony Creek, Conn. The engineer in charge was Isaac C. Buckhout; most of his big brownstone monster has slumbered undisturbed.

In 1967 the architect Jacquelin Robertson proposed roofing over the entire rail line north of 96th Street with a Quonset-hut-like concrete arch supporting a pedestrian mall; that project quickly fell from view.

Walking hard by the viaduct walls is an adventure into an alien rocky wasteland, hummock over hummock of miscellaneous, odd-shaped rock-faced blocks, including rich caramel-colored brownstone for the arches at the cross streets. These are reminiscent of the Arch of Constantine in Rome.

Some of the stone is as crisp as the day it was when first set, but other blocks — some as long as five feet — have been scraped by cars and are as pocked as meteorites. Rows and rows of green plants grow out of the joints, dying back to straw in cold weather.

The four-tunnel 106th Street archway is a wonder to visit, if you can avoid getting hit by a car. At each end are small pedestrian passageways, grim and foreboding. Water from within the viaduct has dripped down into the middle of one of the passages, leaving a frozen stalagmite a foot high. In some places the walls have patches of spongy green moss, in others a crust of soot and water and stone powder, like some fearsome skin disease.

The white efflorescence leaching out of the joints recalls Poe’s “Cask of Amontillado,” in which Fortunato is walled up inside a dank cave covered with white streaks of niter. A soggy lump including a shirt, shoes and a baggy pair of True Religion jeans lends an ominous air, but there is no evidence of anything more dire than a wardrobe malfunction.

And there are the carvings, New York’s answer to the crop circles of the Midwest. Letters, symbols, initials: they are all over, upside down, sideways, seemingly reversed, on perhaps 10 percent of blocks on the arched brownstone sections. A reasonable assumption is that they are the marks of the masons who prepared the stones: WT, P, FW, AT, XL, VII, XII (or is that maybe IIX?). Then there are the symbolists, Easter Seal, Asterisk, Sprig of Rosemary, Telegraph Pole — scores of different marks, most in obviously different hands.

C, Master of the Voussoir (the blocks that make up an arch), did at least half a dozen at 106th Street. One C is perfectly carved, the line shaped and bent as carefully as an engraving. So who, then, carved the scraggly C — was that the School of C? C on a bender? Or another C entirely? Could this be a (“C.S.I.” theme music here) forgery? And was C jealous that XII and Wavy 8 did some voussoirs at 104th Street, poaching on his specialty? Then there are two different carvers, Up Arrow and Down Arrow — or are they the same, just Arrow?

It is strikingly unusual for masons to make their marks on the face of the stone — just why should Asterisk and Telegraph Pole get centuries of free advertising? Were the other 90 percent marked on the back, as these stones should have been? Regardless, why did the railroad allow these graffiti, in peculiar contravention of all custom?

Over the last 20 years Metro-North, which operates the line, has made extensive repairs to the parts north and south of the stone viaduct. But a spokeswoman, Marjorie Anders, says the viaduct itself is in good condition, despite its ragtag appearance.

That is fortunate, because the usual full-bore restoration project would wipe out all the aching ancientness of the thing, like reconstructing the Acropolis all fresh and new. The hand of the restorer is often anything but benign.