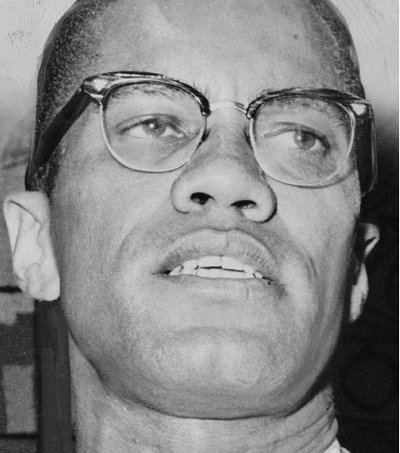

Revolutionary’s evolution – Story of Malcolm X vividly told

Malcolm Little had a tragic childhood. His father, Earl, died in 1931 in a streetcar accident that was quite possibly racially motivated. In 1939, when Malcolm was 14, his mother, Louise, was taken away and confined to a mental hospital. The boy soon found himself in a foster home. By the time he had relocated to Massachusetts in 1941, his jagged spiral had begun. For several years he roamed, wolf-like, between Detroit, Washington, D.C., Harlem and Boston. His activities varied: selling dope, pimping, breaking into homes, hawking snacks on trains. In 1946, the doors of the Charlestown (Mass.) State Prison clanged behind Malcolm Little, putting an end to the foolishness. He would remain there six years.

The reinvention of Malcolm Little – soon to become Malcolm X – began behind bars. “I don’t think anybody ever got more out of going to prison than I did,” he confided. Shortly after being freed, he became a rising star in the Nation of Islam, sent by its leader, Elijah Muhammad, up and down the East Coast to open mosques. Malcolm imbued blacks with pride and offered an ultimatum to white America: Either “the ballot or the bullet” would transform American injustice. After hearing him, many blacks, fed up with living under the American system of apartheid, joined the Nation.

But Malcolm X uncovered proof that Elijah Muhammad had impregnated at least half a dozen young Muslim women. Malcolm’s decision to confront Muhammad set in motion their inevitable and dangerous split. Nation of Islam members believed Malcolm had been usurping Muhammad’s popularity and plotting his own rise; Muhammad himself believed Malcolm was cozying up to mainstream civil rights leaders. Malcolm’s celebrated visit to Mecca, which forced him to rethink his separatist leanings, further antagonized many Nation members. He had embarked on the path that led to his murder by Nation of Islam members on Feb. 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem.

Malcolm X’s life has inspired filmmakers, writers, painters, rappers and dramatists, yet much about his murder has remained a mystery. Now we have Manning Marable’s “Malcolm X,” a groundbreaking piece of work. Marable, a historian who died on the eve of this book’s publication, convinced people who had been silent for decades to sit for interviews. He also drew upon oral histories, dusty police reports and FBI and CIA documents. The result is not just a biography, but also a history of Muslims in America and a sweeping account of one man’s transformation – and of the conspiracy, abetted by police inattention, that took his tumultuous life. The tension toward book’s end – when Malcolm was trying to figure out who might murder him – is so gripping it nearly soaks through the pages.

At first, Elijah Muhammad saw Malcolm X as a gifted disciple with great potential and self-discipline. But Muhammad prided himself on getting the Nation to look inward. In contrast, political currents intrigued Malcolm, who particularly admired Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. “Elijah Muhammad,” writes Marable, “could maintain his personal authority only by forcing followers away from the outside world; Malcolm knew that the Nation’s future growth depended on its being immersed in the black community’s struggles of daily existence.” Bypassing traditional civil rights leaders and often deriding them as “Uncle Toms,” Malcolm appealed to urban blacks in the ghetto. He warned in a 1957 speech that if the “Negro intelligentsia” didn’t do something about blacks being murdered in the South by white supremacists and discriminated against in the North by business owners, “the little man in the street will henceforth begin to take matters into his own hands.” Soon the FBI and the New York police were tracking Malcolm’s movements and placing undercover agents inside the Nation.

Two incidents, in addition to Elijah Muhammad’s infidelities, exacerbated the split with Malcolm X. The first came in 1962, when Ronald Stokes, an unarmed Muslim who was a friend of Malcolm’s, was shot and killed by Los Angeles policemen in a parking lot. Malcolm wanted revenge, but Muhammad urged against it. Malcolm eventually joined with L.A. civil rights leaders to protest police brutality, a move that infuriated Muhammad. The second, more serious incident came in the aftermath of President Kennedy’s assassination. Malcolm tried to blame the killing on U.S. military violence abroad. Muhammad was livid. He believed that the authorities would strike back at black Muslims, particularly those in prison, for Malcolm’s words. He suspended Malcolm, and the suspension led to a convulsive split, with Malcolm eventually forming his own organizations.

Marable persuasively shows us the tightrope that Malcolm walked in the early 1960s. He would belittle civil rights leaders but also, after breaking with the Nation, would seek common ground with them. Marable does not shy from Malcolm X’s repugnant statements and actions, such as dismissing well-meaning whites who wanted to join his crusade; and his bizarre negotiations with the Ku Klux Klan, in 1961, to buy land for blacks to live on.

Malcolm had also begun working on his autobiography with Alex Haley, one of the few black writers able to get assignments from mainstream magazines. (One must not forget that at the time of Malcolm’s struggles, the fields of law, medicine, journalism, university teaching, banking, finance and many others were difficult for American blacks to penetrate.) The scenes of Haley and Malcolm sitting in Haley’s New York apartment – two black cats from different sides of the political divide – are priceless: Though glum about death threats and the safety of his family, Malcolm rises and jitterbugs to show Haley what he was like when he was known as Detroit Red. Marable challenges Malcolm’s autobiography but offers no real surprises.

Marable works the reinvention motif into the book with authority. He accentuates Malcolm’s fabled and life-changing journey to Mecca. “Malcolm was quick to credit Islam with the power to transform whites into nonracists,” Marable writes. “This revelation reinforced Malcolm’s new-found decision to separate himself completely from the Nation of Islam, not simply from its leadership, but from its theology.”

Toward the end, many Nation of Islam members had ceased calling him “Brother Malcolm”; Malcolm X was now “a heretic.” His house in Queens was firebombed. His murder was plotted – though not with the approval of Elijah Muhammad, Marable points out – a year in advance. Marable examines the evidence against a number of suspects and abettors, including informers, inefficient NYPD officials and the murderers themselves. This is tragic and shocking material: Some of the killers apparently remain at large while two of the convicted may have been innocent.

My only criticism is that Marable did not tell us enough about Malcolm’s family in the years following his death. That family has suffered much pain. In 1995, Qubilah, one of Malcolm’s daughters, was charged with hiring a hit man to murder Louis Farrakhan, who had sided with Muhammad during the Malcolm contretemps. The case fell apart in court. Malcolm’s widow, Betty Shabazz, died in 1997 from injuries suffered in a house fire set by her grandson Malcolm, Qubilah’s son.

It will be difficult for anyone to better this book. It goes deeper and richer than a mere homage to Malcolm X. It is a work of art, a feast that combines genres skillfully: biography, true-crime, political commentary.

It gives us Malcolm X in full gallop, a man who died for his belief in freedom, a man whom Marable calls the “fountainhead” of the black power movement in America.